We are preparing a whole lot of stuff to go in our Lyrebird Project part of the Projects site. I hope we can put up grabs/sections from my  radio play and Josephine’s sound poem. I haven’t broached this with Tom Kazas, our sound (of mind and character) man, but I hope we can recreate here some of the experience of listening to the different layers of the radio play as they have been assembled. At the moment, in Lyrebird you’ll find a poster we prepared for the Turbulence 2 symposium held at Deakin in late October.

radio play and Josephine’s sound poem. I haven’t broached this with Tom Kazas, our sound (of mind and character) man, but I hope we can recreate here some of the experience of listening to the different layers of the radio play as they have been assembled. At the moment, in Lyrebird you’ll find a poster we prepared for the Turbulence 2 symposium held at Deakin in late October.

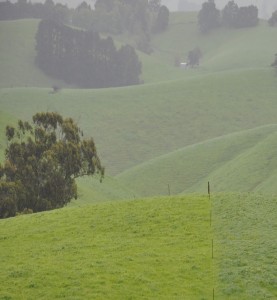

The image accompanying this post is a grab from the poster. I’ve used it here because the image somehow captures an aural quality which we attempted to replicate in the play – windswept maybe, empty, yearning?

Tom will have far more interesting things to say than me on aural theory, but I can talk a little about how radio drama uses sound. Tim Crook’s in Radio Drama: Theory and Practice refers to the ‘assumed hierarchy of the senses’ – that is, that we privilege, as a default, vision above all else. But of course sound precedes vision. We hear in the womb, and establish strong primal bonds through sound. The assumed hierachy opens out to the relationship between film and radio as artforms, where in the history of such things radio becomes a quiant device to be superseded by the domestication of the visual (ie television). But somehow radio drama lingers.

Radio National’s Airplay always has some interesting stuff to listen to, but for a real set of incredible resources go the BBC’s Writer’s Room.

One of the great strengths of radio – or let’s be more broad and in fact accurate, and call it ‘audio’ – is its dimensionality. Essentially when we watch a film we are removed from the action by the necessary presence of a screen. Our imagination does manage to cross the space, but never completely. This is perhaps the nature of visual observation. Sound is far more immersive. The best radio drama exploits this, where we can find ourselves within the thoughts of a character while also experiencing a panorama beyond. And film largely works to shut down the imagination of the spectator, but audio enlists this imagination to construct the visual dimensions of the drama.

This is all quite basic, but the fresh insight I’ve gained from the process of making (rather than just writing) has been the role that sound plays in the construction of a narrative. I know this because the first thing that appeared on tape was dialogue/speech, and hearing this gave me a moment of mild panic – that listening to the whole play right through convinced me that this thing had no narrative cohesion. Even the insertion of sound effects only helped a little. It was the third stage, the soundscaping that created the narrative. This might be something as simple as positioning a character in relationship to the implied position of the listener. Or it might be creating narrative cues which move the listener through different timeframes and into different headspaces.Or is might even be inserting a space (as we have done) into a piece of speech to create a moment of subtext or to shift focus.

We shall discuss this further.

A tangential thought on the sound of narrative:

It must be that concentration of life: a forest, whose sound is so evocative to the human ear, that so easily creates a sense of place, especially in a radioplay. No real surprise. Together with the Lyrebird, we’ve been listening to forests for eons.

Imagine if you will a theatre, where the audience has quieted down. The stage curtain is drawn to reveal: a cast of Lyrebirds. Nothing else. They proceed to not only reproduce the sounds of the forest and the particular sound effects, but also the voices and dialogue of the drama. The whole three act thing.

This idea seriously entertained our attention for a while as we were working on the radioplay. The appeal is obvious. The Lyrebird, being the mimic par excellence, might carry the whole drama, having witnessed the very same scenes that Patrick has described in his script.

No such luck, but also, a much grander opportunity.

I remember the first time I was able to hear the radioplay, almost fully soundscaped, from start to finish, uninterrupted by the need to stop and adjust a detail. It rooted me to my chair. The sheer power of sound to create associations and imagery, allowing me the freedom of my own associations and imagery; it was a liberation. No domestication of the visual here. No tyranny of the over-supplied.

So we dismissed the cast of Lyrebirds, knowing we were able to create the space for ourselves. And what a space! This is space par excellence, even more riveting than the real thing. A space where the contours shape the narrative, but are also shaped by it. A space more malleable than the real thing. The imagination, a better home for reality.

Tom

Thanks Tom,

Many years ago I was walking through a forest with Dr Doug, distinguished ornithologist. Doug ‘spotted’ pretty much everything by ear rather than sight. So while I strained to see what was there and tried to compare the still picture in the field guide to the hopping, flitting thing in the canopy, he just listened. This struck me as an indicator of the flexibility and accuracy of audio, and this of course is how birds get around and communicate. It’s a kind of cloak of invisibility as well – when I stop making a sound I disappear, but when I sing my presence fills the space around me.

Patrick

Tom and Patrick,

Your thoughts about the evocative sounds of the forest and sound creating a sense of place have made me think about what Paul Carter was writing about in his book, The Sound In Between. He writes: “To sound the space is to denominate it a place: it is to mark it as a historical event” (1992,p.12).

And he continues:

“The sound in-between does not originate on one side or the other. It is provoked by the interval itself. In this sense it resembles a name given to a space: the verbal gestures of first contact, the stumbling mimicry of the other person’s speech, look forward to places. Such a sound is not then simply a performative strategy. The mimicry it employs is not meant to parody communication, to undermine assertions of authority. It is a historical device for keeping the future open…”(1992:12 -13).

The above quote is included in the article Tom and I co-authored on our previous collaboration ‘Something like an emergency’. In that context I was speaking about the spaces in which voice and music or sound converge by the chance and coincidence afforded by improvisation.

What’s really interesting is that Carter mentioned mimicry in birdsong in this discussion and if my memory is accurate, a particular South American parrot. In the quote above he was also referring to first contact between invader/settlers and indigenous peoples.